Soaring above the colossal spikes of the Canadian Rockies, Peter Fuhrman's sixth tingled rapidly.

Tied to a long-line harness flying past scarred limestone rock beneath a buzzing helicopter, the mountain rescuer accepted the personal risk because he knew speed was often the difference between a rescue scene or a body recovery.

“All us mountain guides know there’s danger there,” he said. “You get this feeling.”

Once an alpine specialist in nine national parks including Banff, Yoho and Kootenay, the mountain man kept a photographic memory for rescues he was closely involved in, but one became special.

In 1971, an ailing man’s time was running out after a rock chunk had fallen and crashed on the victim’s head at Mount Edith in Banff National Park. Gliding through the summer breeze towards the iconic mountain, there was no indication at the time, but Fuhrmann was on the verge of Canadian history.

Throughout his 25-year career, whether leading rescues in waist-deep avalanche terrain snow, or engaging in political sway with “black suits in Ottawa” using a quick wit, Fuhrmann’s sharp instinct was key in revolutionizing mountain rescues in the Great White North.

Every year, organizations such as Kananaskis Country Public Safety Alberta Parks (KCPS), Parks Canada, and Alpine Helicopters Inc. respond to hundreds of mountain incidents.

Most end without fatalities and since the early ’70s, missions have called for the “heli-sling” method to be used, where a pilot flies safety specialists into inaccessible areas in order to lift out a distressed person.

The convenience of the technique was an original reason Fuhrmann wanted to bring the European equipment and method to Canada — even if he was met with Ottawa’s resistance.

Fuhrmann’s life at age 87 is simpler than it used to be. Retired since 1991, the days when he keenly lept off mountain edges attached to a helicopter’s cable passed long ago, but that part of the mountain rescue pioneer’s life is “still vivid in my mind,” he said.

In 1968, Fuhrmann took over as alpine specialist and was given a horse and crew to cover Canada’s flagship national park, Banff. The country’s mountain rescue system was terribly inefficient, with expensive rescues consuming excessive resources and patients sometimes dying needlessly during transport.

“We ran 151 rescues in June, July and August and part of September,” Fuhrmann said. “I was in the field morning, night, all day, constantly … it was a breaking point.”

Everything changed when neighbour, dear friend and Banff legend, Bruno Engler, handed Fuhrmann a European magazine that featured proven heli-sling methods and techniques that were revolutionizing the mountain rescue industry. It was Fuhrmann’s light-bulb-going-off moment: the heli-sling was cost efficient, fast and exposed fewer people to danger.

Fuhrmann flew to Germany to meet with inventor, Ludwig Gramminger, where they “drank a lot of beer, discussed the whole system and made a few diagrams” before the Banff alpine specialist was given a rescue seat and all the information on how to successfully perform it.

The Canadian government was apprehensive, though, due to an incident following a climbing death at Mount Yamnuska, near Canmore. A helicopter pilot, using a sling, attempted to lift the victim off the mountain, but when the load started swinging on the long-line underneath, the frazzled pilot panicked and dropped the bagged body onto the field below. Ottawa said there’s “no way we’re going to go under the machine because we see what would happen.”

Regardless, Fuhrmann and local pilot, Jim Davies, continued practicing heli-slinging. Returning from Jasper in 1971, Fuhrmann got his chance to try out what he’d been lobbying for. A hiker took a bad spill near Pinto Lake, off Highway 93 north, and driving south with the heli-sling equipment in his vehicle, Fuhrmann listened to muffled radio voices from emergency crews discussing the situation.

“The talk was of whether or not they were going to get him out, and if they couldn’t by the end of the day, he was likely to die,” said Fuhrmann.

He pulled over at the staging area, where a helicopter was landed, and approached the pilot to explain the process of heli-slinging the injured hiker out using a metal stretcher. Open to trying, the pilot agreed to get close enough to the injured hiker, drop off Fuhrmann, then lift the pair out of the area. Fuhrmann loaded the patient in the stretcher and they were lifted back to the staging area.

Everything was working perfectly, until the radio crackled in Fuhrmann’s ear and the concerned pilot explained, “you know, I’m going to have a big problem setting you down because you’re too heavy with the guy in the stretcher.”

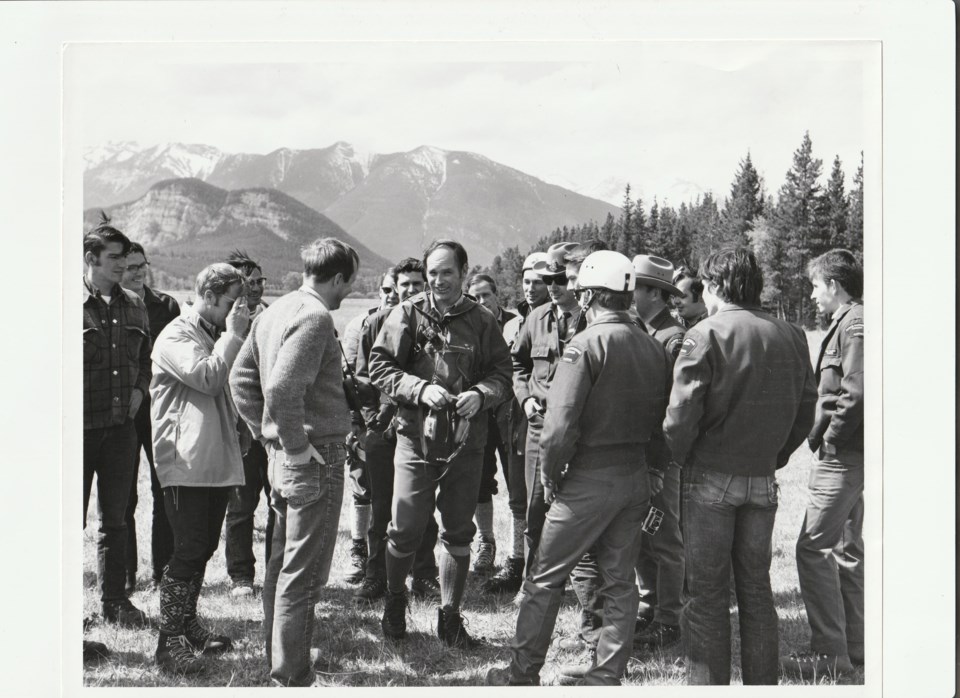

Thinking fast, Fuhrmann radioed in to eight wardens waiting at the staging area, and told them to be ready to catch the stretcher to take the extra weight off. With a smack into 16 hands, the innovative problem solving worked like a charm and saved the man’s life. It was the first ever heli-sling rescue in Banff National Park, but less significant than the second.

The rescue that changed it all

Bursting into the alpine specialist’s office, a frantic Canadian Armed Forces member explained how a rock had fallen on a member of the unit, bloodying him and leaving a “big hole in his head.”

It was Aug. 5, 1971 when Fuhrmann conducted the second heli-sling rescue, at Mount Edith. It was in a “bad flying area” of the mountain, but Davies and Fuhrmann were prepared to perform the still-outlawed practice.

When Fuhrmann touched down on the mountain’s edge, the injured man sat hunched over on scattered rock bits, with a wool bag covering his battered head. Fuhrmann calmly attached the man to the stretcher with the help of the military unit, connected to the helicopter’s cable, and flew off towards the hospital.

The experience Davies and Fuhrmann gained while practicing was apparent as the pros successfully carried the severely-hurt Armed Forces member to the old Banff hospital.

After the rescue, Fuhrmann ensured he received a hand-written certificate from local doctors stating the injured man would have died had he not been rescued in this fashion.

“After that, the heli-sling was absolutely approved with all superintendents in national parks,” Fuhrmann said. It was the beginning of modern mountain rescues as they are known today.

Modern era heli-slinging

Bonded by a common cause, modern mountain rescuers have each other’s backs whether they’re floating in the sky, or huddled on the edge of a snowy cliff.

Working together, pilots and rescuers formulate a plan for the safest way to access each patient, and like the olden days, pilots and rescuers share a bond.

For three local rescuers, pilots Todd Cooper and Perry Hirsch of Alpine Helicopters Inc., and KCPS safety specialist, Mike Koppang, there’s an associated risk when they suit up and head towards a scene, but they count on each other to make it work. Helping others in need is apart of the job the rescuers are absolutely committed to.

“That’s why we signed up to be rescue pilots — to be there for the community and using our skill set to help our community,” Hirsch said. “We’re going to help with your problem as efficiently and safely and quickly as we can, not causing harm to us or the aircraft.”

“The danger side of it is you’re not trying to create another rescue while you’re out doing the first rescue,” Cooper said, who is a second-generation mountain pilot and rescuer.

During avalanche rescues, it’s not uncommon for safety specialists to stay hooked to the hovering helicopter’s cable in preparation for a worst-case scenario.

“If an avalanche comes down, we’re out of there. We don’t do that all the time, but [it happens] a few times a year,” Cooper said.

One instance where catastrophe was avoided occurred in June 2017. An Alpine Helicopters pilot made an emergency landing near Mount Yamnuska during a rescue after the helicopter blades struck the mountain’s rock face 900 metres in the air. The terrifying incident was the only time in Alpine’s history this has happened, but showcases the immense potential danger of each rescue.

“We got lucky,” Cooper said. “Thankfully it all worked out well.”

Heli-slinging, however, is generally safe if pilots and specialists are fluent in the practice.

“We train in this step very frequently,” Koppang said. “So you don’t let the excitement of the moment run away on you; you want to be able to notice every little thing and you want to be able to move slowly and effectively and efficiently.”

Giving back to the community and aiding those in need is rewarding for mountain rescuers.

“The rescue flying, in hindsight, is a huge reason why I started doing it,” Cooper said. “Maybe it took a while to realize that, but it’s pretty important to me, the flying that we do here, and it’s a team here. We all really work well together so that’s kind of a neat aspect of it.”